Book Description

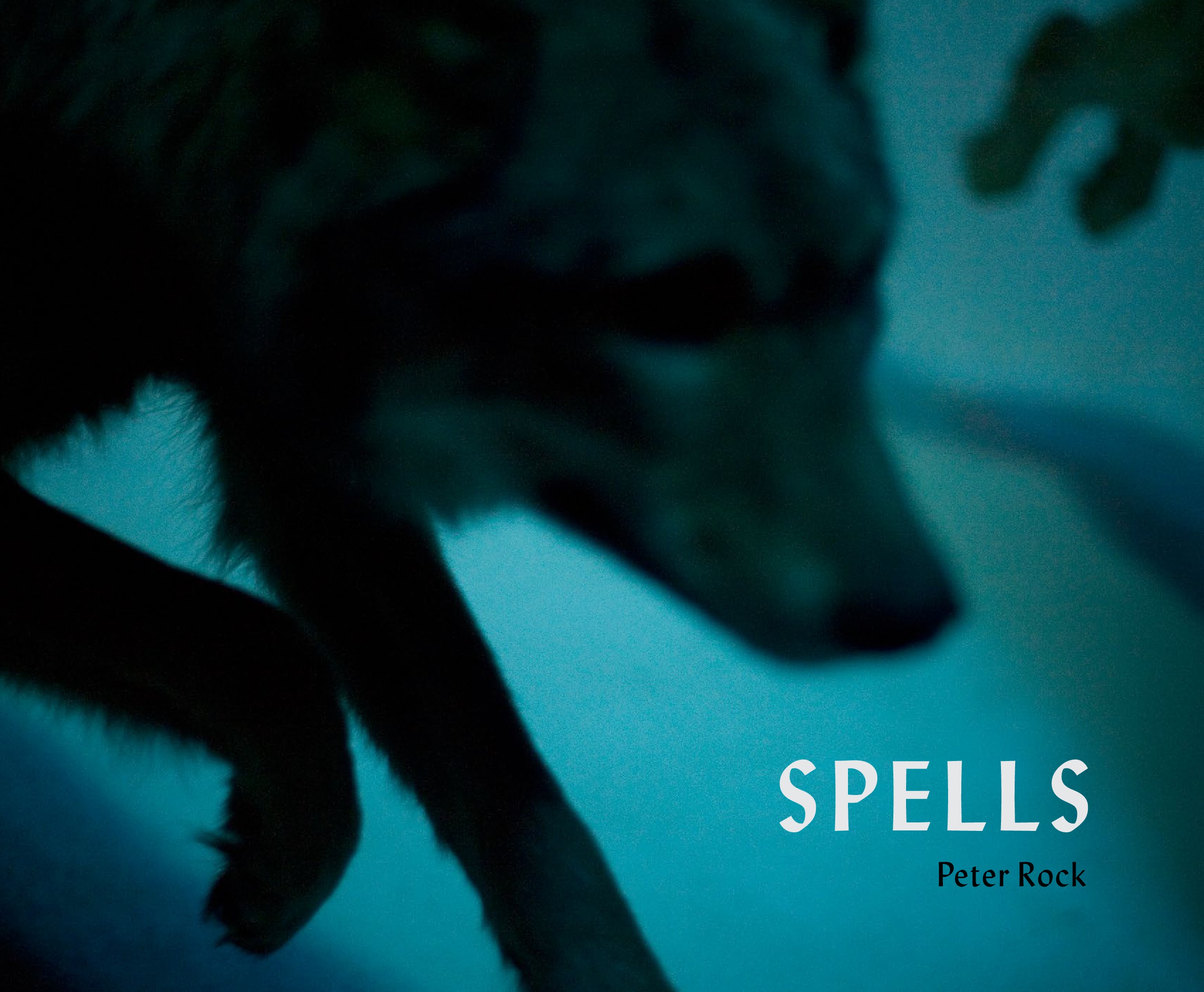

Twenty years ago, while working as a security guard in an art museum, Peter Rock staved off the job’s inherent boredom and loneliness by trying to make up a story for each photograph, painting and object in the museum. A few years ago, reminded of the pleasures and play that he felt in danger of forgetting, he began to envision a similar project.

As he explains, “First, I found photographers whose work I was drawn to, and contacted them with a very hypothetical and tentative description of what I was doing. Somewhat arbitrarily, I decided that five photographers would be a good number; I was gratified that the first five I contacted were excited to join me. Next, I let these photographers know why I was drawn to their work, noted some images I really admired, and shared some of my previous writing with them. I asked them to send me 20–30 images; of these, I chose five at a time, and proceeded incrementally, generating the specific stories as I went.

The images are not merely illustrations for a pre–existent story, then, but the conditions and possibilities and limitations of how they proceeded. The images came first. One way to think of it is that the stories herein, and the larger story they become, were already embedded in the photographs. My attention and intuition acted as a kind of excavation that brought them to the surface, into words.”

The texts range from narrative to prose poem, from folktale to rant to reverie to an essay written by a fourth grader. The overarching story follows three friends who have recently graduated from high school; it explores their relationships and how things change when they become entangled with an elderly widower who claims to have dreamt of one of them. The ensuing drama explores the relationship between dreams and waking life, between the head and the heart, between shadows and their bodies, between the living and the dead.

Praise For This Book

"Rock's prose calls to mind Kazuo Ishiguro, not just for its spareness but also for its mix of wonder and creepiness." —New York Times"Peter Rock (is) a master at making strange behavior and strange situations utterly believable and filling them with unbearable suspense." —Ursula K. Le Guin

"A fascinating endeavor."" —Kirkus Reviews